We don’t need drugs or vaccines to stop the Covid-19 pandemic. We can use something that is already available and at our disposal: rapid point-of-care and home diagnostics combined with contact tracing and isolation of possible transmitters.

Backed by the right technology and strategy, testing can be used to detect the virus at its most contagious—and stop the people who carry it from spreading it to others. In the United States, this is currently far from the case.

Barriers like the cost of a single test, which can range from $50 to $150, and uneven spread of testing sites, which for some demand long commutes, make testing a rarity reserved for worst case scenarios, rather than a safety measure accessible to all. The long waiting times render the results moot for many.

Among the nearly 200 Covid-19 tests authorized for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are already several technologies that can make testing faster, cheaper, and more convenient. These new methods must become the basis of a nationwide testing regimen in which tens of millions of people are tested day in and day out.

Part one: the technology

PCR tests, named for the polymerase chain reaction used to magnify samples and detect viral RNA in labs or research centers, have so far been the gold standard and bedrock of most testing efforts. Though more accurate than most Covid-19 test types by a wide margin, the turnaround time for a PCR test result is typically a few days at best and a few weeks at worst. Such a delay impedes our ability to tally infections as they’re actually happening, meaning most national and even local case counts underestimate the rate at which disease is circulating in our communities at any given time. It also means that people who might be at the vey peak of their contagiousness leave the testing site ignorant, unknowingly continue to infect others, sometimes many others.

Data collected in Spain, the United States, and several other countries using antibody tests, which pick up on the presence of Covid-19 specific antibodies in the blood, offers clues as to how great the gap between confirmed and active Covid-19 infections actually may be. SeroTracker, a Canadian analytics hub that aggregates this data, estimates the prevalence of Covid-19 antibodies in the U.S. population to be five percent on average—meaning the national confirmed case count that recently surpassed five million, a bit more than one percent of the country, likely represents only a fraction of infections currently active. While antibody tests are useful in shedding light on the true scope of an outbreak, they can only do so in hindsight, when infections have already happened. There’s also no knowing how many infections are left out because the carriers are unsuspectingly asymptomatic and therefore have no reason to seek out testing.

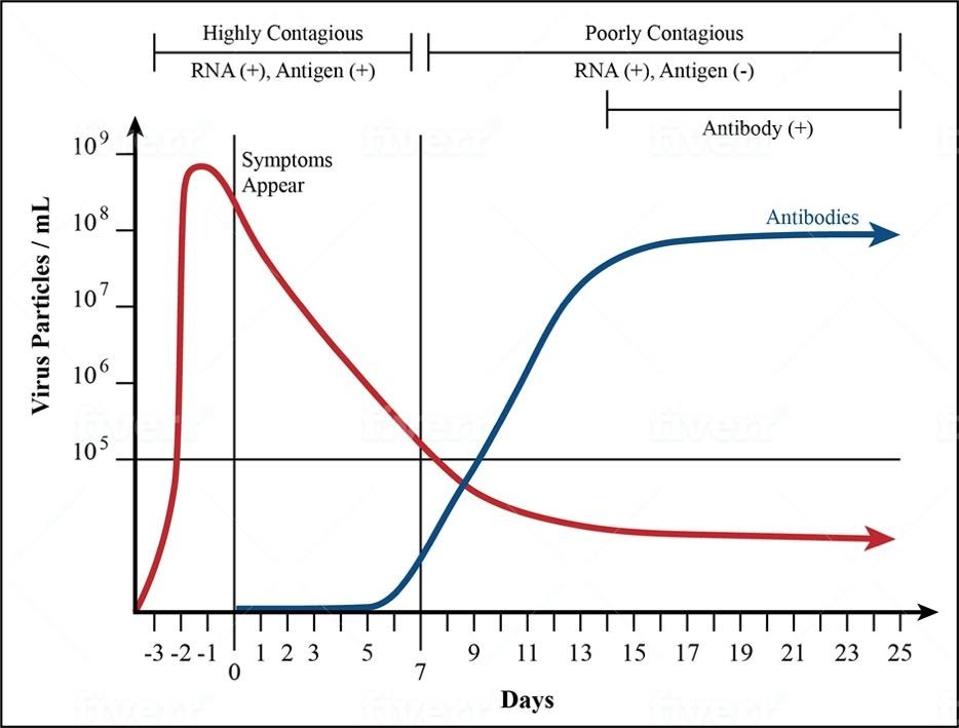

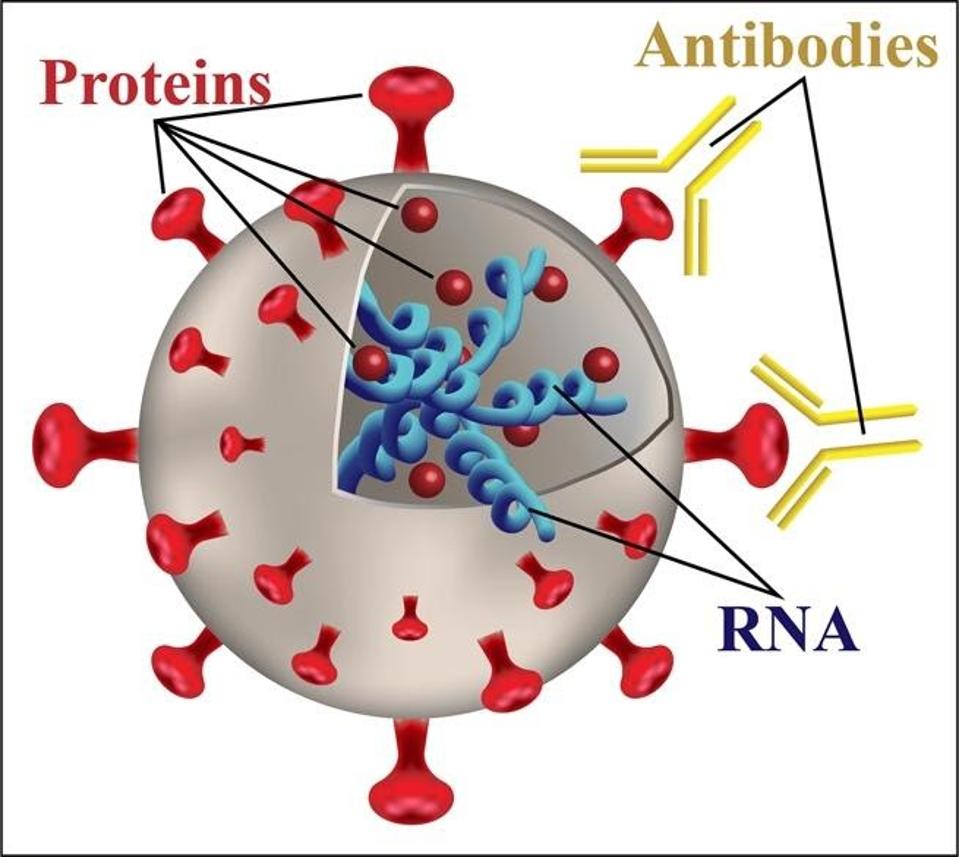

To make testing a preventive, rather than reactive, form of disease control, we need speed and convenience. Such is the advantage of using antigen tests, which measure SARS-CoV-2 by way of viral proteins, or antigens, and don’t require the extra step of in-lab processing—hence a turnaround time as fast as 15 minutes. The tradeoff, as might be expected, is sensitivity, and an antigen test is indeed more likely to miss some who would test positive by PCR. But when it comes to controlling or preventing community spread, sensitivity isn’t necessarily the most significant factor. Data from preprint studies shows that the concentration of the Covid-19 virus in our nasal passages and throat is at its highest from the day before we develop symptoms to seven days after (see Figure 1). This is when we’re most likely to pass the infection on to others. From Day 7 onward the amount of virus in the body diminishes, as does our ability to transmit it—though most people remain PCR-positive for many days. Why this is so is a biologic mystery waiting to be solved, but the fact remains that if you give someone a rapid diagnostic early enough, their body will have so much virus a sensitive test won’t be necessary.

FIGURE 1. Studies show that the concentration of the Covid-19 virus in our nasal passages and throat is at its highest from the day before we develop symptoms to seven days after. This is when we’re most likely to pass the infection on to others.

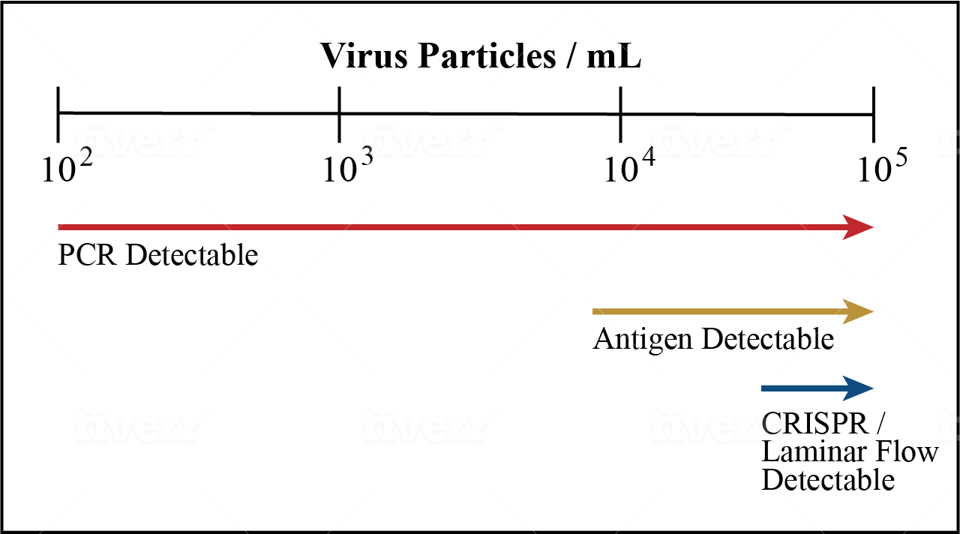

FIGURE 2. Comparing the limit of detection for different Covid-19 test types.

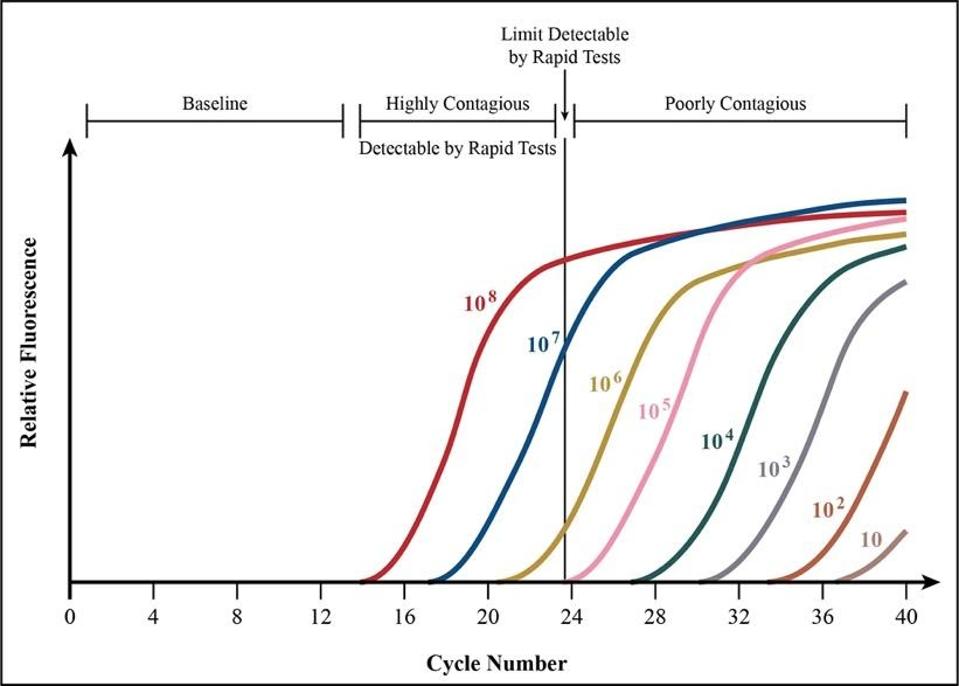

Given these findings, the most useful tests for mass screenings are those that detect the amount of virus particles associated with transmission, estimated to be about 100,000 or 105 per millimeter (see Figure 3). Fortunately antigen tests and other rapid diagnostics currently in development are up to the task (see Figure 2). One uses CRISPR technology to analyze nasal swabs or saliva samples for traces of viral genetic material. Another relies on the same paper-based laminar-/lateral-flow immunoassays as disposable pregnancy tests and could potentially give users the option to test themselves before school or work in the comfort of their own homes. While no rapid diagnostic yet has received regulatory approval for at-home or over-the-counter use, the FDA has recently amended its protocols to clear the path forward for such products. Once they’re brought to market, it will no longer be the case that the only people tested are those who act out of suspicion of exposure or infection. These tests will be for everyone—healthy and asymptomatic individuals included.

FIGURE 3. Data on PCR cycle times offers more evidence that testing earlier in the disease course might intercept contagion at its most infectious.

FIGURE 4. A model of a virus.

Part two: the strategy

I believe that each test should cost no more than fifty cents. That was the price of the Abbott rapid antibody tests that Egypt used to screen its entire population, ages 12 and older, for hepatitis C. Results should be available within 5 to 15 minutes. The low cost and speed should allow every schoolchild, every teacher and everybody working with others to know whether or not they are an asymptomatic, contagious carrier. It would allow public health authorities to identify and isolate those who are most contagious. The effect on the pandemic will be immediate and dramatic.

With mass deployment of less sensitive, but rapid and easy-to-use diagnostic tests that deliver results within minutes at the doctor’s office or at home, anyone infected will know almost immediately, before symptoms even begin to show, to stay at home and isolate—stopping the spread of the disease in its tracks and clearing the way for faster containment. Following up positive tests with contact tracing, a technique that was critical to mitigating Covid-19 in Singapore and South Korea, would ensure that recent contacts of the infected would do the same. This would be especially helpful in both removing so-called super-spreaders, or infected people with high viral loads, and freeing those who may test positive, but don’t have enough virus in their bodies to be infectious.

One way to mobilize this strategy is through the two-step testing method currently underway in India, where confirmed cases now exceed two million. The first step is to conduct widespread rapid tests at existing testing facilities and, once the technology is authorized and available, in our homes. Those who test positive with a viral load at or above 103 viral particles per millimeter are assumed to be infected and instructed to self-isolate at home, where they can be monitored by local health authorities. Within 24 hours a contact tracing team interviews them about recent contacts who may have been infected, all of whom are brought in for testing as well. Those who test positive but carry a viral load below 103 particles per millimeter are contact traced, but aren’t required to isolate, as they’re beyond the threshold of infectivity. Those who test negative, on the other hand, proceed to the second step: the PCR test with a slower turnaround, but more accurate result. They must also quarantine until the PCR test results confirm or disprove their negative status—unless they carry viral load below 103 particles per millimeter, in which case they must be contact traced but needn’t isolate.

Insofar as antigen tests are also cheaper to manufacture and cheaper to purchase than PCR tests, they make an ideal tool for scaling up testing efforts at the community and national level. If mobilized through coordinated efforts like the recently announced interstate testing compact between seven state governments, test makers, and the Rockefeller Foundation, these speedy diagnostics could become truly accessible for a low price at a large scale. Taking such a strategy nationwide may seem ambitious, but meeting the challenges of the current crisis will require nothing less.

The strategy of “test, trace, isolate” is nothing new. What’s different now is we have the technology to make it possible at a low cost and in a short amount of time. If we continue to underinvest in testing, we consign ourselves to repairing damage that has already been done—rather than preventing it in the first place.