Random variation is an essential component of all living things. It drives diversity, and it is why there are so many different species. Viruses are no exception. Most viruses are experts at changing genomes to adapt to their environment. We now have evidence that the virus that causes Covid, SARS-CoV-2, not only changes, but changes in ways that are significant. This is the seventeenth part of a series of articles on how the virus changes and what that means for humanity. Read the rest: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, part seven, part eight, part nine, part ten,part eleven, part twelve, part thirteen, part fourteen, part fifteen, part sixteen and part seventeen.

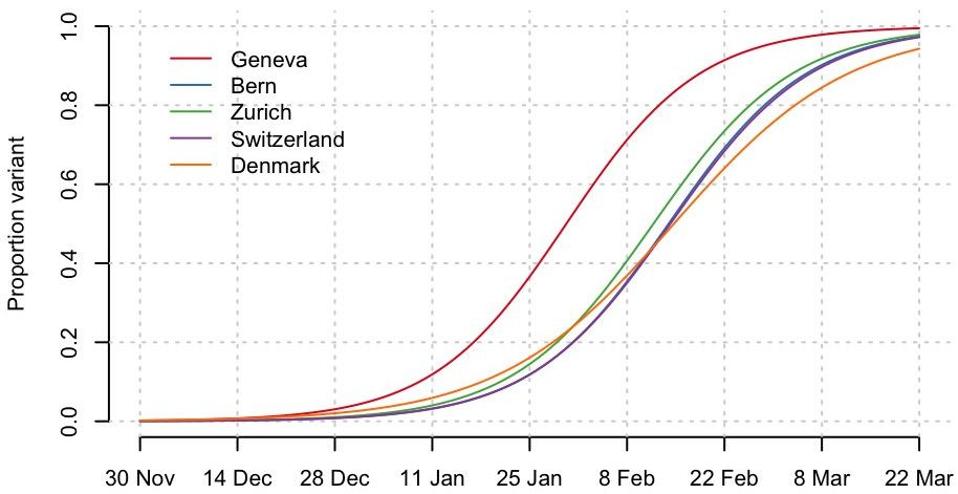

In a prior column for Forbes, I detailed how the rapid spread of variants across Europe should serve as a warning for the US. I explained how data from the UK, Denmark, Belgium and Switzerland collectively demonstrate that the UK B.1.1.7 variant predictably overtakes previously dominating strains progressing from 20% to 80% of the circulating viruses in just 4 weeks. The below model (Figure 1) shows that those countries could be facing new waves of epidemics as early as mid-March.

The CDC has now issued a similar warning in the form of two new reports, suggesting that variants could cause a rapid rise in Covid-19 cases in the US, based on international and local examples. In one report, the CDC has used the international example of the country of Zambia in East Africa as a warning. After 3 months of relatively low case counts, Covid-19 cases began rapidly rising throughout Zambia in mid-December 2020. Among the 23 positive Covid-19 specimens collected during December 16–23, 2020 by the University of Zambia and PATH, 22 (96%) were classified as the B.1.351 variant demonstrating a clear link to increased transmissibility by the B.1.351 variant. The below chart (Figure 2) tracks the evolution of Covid-19 cases in Zambia throughout the pandemic.

The second CDC report, details an investigation into the spread of the first identified cases of the B.1.1.7 UK variant in Minnesota and urges the public to engage in “mitigation measures such as mask use, physical distancing, avoiding crowds and poorly ventilated indoor spaces, isolation of persons with diagnosed COVID-19, quarantine of close contacts of persons with COVID-19, and adherence to CDC travel guidance.”

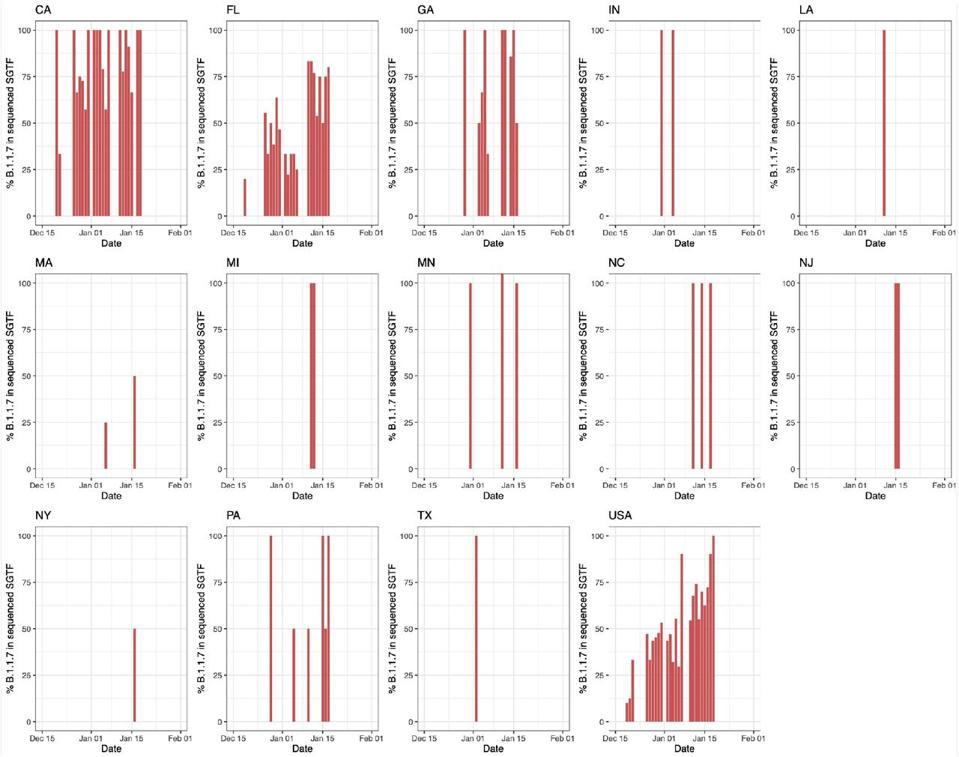

A recent preprint study gives a more thorough picture of the spread of the B.1.1.7 UK variant throughout the U.S. The study used the RT-qPCR testing anomaly of S gene target failure (SGTF), first observed in the U.K. as a proxy for B.1.1.7 detection. Through this method, they found detection of the B.1.1.7 UK variant in the U.S. from December 2020 to January 2021 increased at a logarithmic rate similar to what has been observed overseas with a doubling rate of a little over a week and an increased transmission rate of 35-45%. The study shows that community transmission enabled the B.1.1.7 UK variant first detected in late November 2020, to spread to at least 30 states as of January 2021. More recent CDC data shows the B.1.1.7 UK variant has been detected in 41 states and Washington, DC. The below chart (Figure 3) shows the rapid spread of the B.1.1.7 UK variant in different U.S. states and the U.S. overall.

In addition to studies on the UK B.1.1.7 variant, we have already seen evidence of how quickly the California variant B.1.429 and the collection of viruses with the mutation 677 spreads through the population. It is clear from these domestic and international examples that the U.S. needs to act fast to stop a potential rapid rise in Covid-19 cases stemming from new variants.

Americans are becoming complacent as cases decline, but now is not the time to be rolling back restrictions as some states are. As seen in Figure 3, Florida has one of the highest concentrations of the UK B.1.1.7 variant, yet Governor Ron DeSantis has recently rolled back Covid-19 restrictions entirely and has not enforced a mask mandate. A mistake which could have dire consequences. The UK B.1.1.7 and South African B.1.351 variants have shown evidence of increased viral load which is associated with increased disease severity and mortality.

Below I outline the public health measures that need to be taken to protect ourselves against the new variants based on what we currently know:

Behavioral protocols

The UK B.1.1.7 and South African B.1.351 variants have proven to be more transmissible which means fewer virus particles are needed to transmit the virus. When asked, I recommend the use of N95 masks with face shields to protect yourself and others. Cloth masks may no longer be sufficient as it is difficult to maintain the tight seal needed, especially in children.

Everyone needs to accept a vaccine when available to them, but a vaccine is not a get out-of-covid free card. Currently, we know that Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine loses some potency against the South African B.1.351 variant. Until we have comprehensive data on the efficacy of all approved vaccines against the new variants, those who are vaccinated should still take precautions such as mask-wearing, physical distancing, and avoiding indoor activities where possible.

Travel restrictions and incentivized quarantining

Six of the first eight people first identified with the UK variant B.1.1.7 in the CDC Minnesota investigation reported recent travel (three international and three domestic, none had traveled to the UK) further emphasizing that it is absolutely critical to avoid travel. Unfortunately, US Airports have seen some of their busiest days since the holidays. The TSA reported it screened more than 967,000 people at airports on Monday and a further 738,000 people on Tuesday. There needs to be better communication about the serious risks of traveling while these highly transmissible variants are developing. For those who cannot avoid travel, the CDC needs to stipulate mandatory testing for both domestic and international traveling, as currently it only requires the latter.

I have repeatedly advocated for incentivized isolation, in which those who have or been exposed to or infected with Covid-19 are paid to quarantine at home, removing the potential burden of lost income. Those who cannot isolate safely at home should be offered a free hotel room, like the program run in NYC. With the highly transmissible nature of some variants, this has never been more critical.

The length of quarantine should be based on the latest data available on the period of contagion for different variants. A small, not yet peer reviewed study was recently released by Harvard which analysed the daily PCR tests of 65 NBA players all infected with SARS-CoV2, seven of them infected with the UK B.1.1.7 variant. I have an The mean duration of overall infection for the players infected with the variant was 13.3 days compared to the players infected with SARS-CoV2 who had a mean duration of infection of 8 days. While a relatively small sample, we should proceed with caution and extend our quarantine period to three weeks like China has done, until we have more comprehensive data.

A comprehensive genomic surveillance system

Biden’s investment of $200 million in virus genome sequencing is a welcome start, but it does not go far enough. Genome sequencing is one of our most important tools to track the developing variants and emerging threats, make timely public health decisions and update vaccines. We should also be tying genome sequencing to information such as robust contact tracing to more fully understand how the variants are spreading.

We should be aiming to replicate the approach of the COG-UK Consortium and sequence at least 5-10% of all virus samples. The Biden Administration estimates that the $200 million investment will increase the sequencing capacity of the CDC from about 7,000 samples per week to approximately 25,000. If case rates remain consistent (which is unlikely) this number barely puts us at sequencing 5% of virus samples.

A paper in Cell, encourages strong coordination between the entities performing diagnostic SARS-CoV-2 testing, the labs with the expertise, capacity, and resources to conduct relatively large-scale sequencing and computational groups who can process and analyze the large genomic datasets for an optimal genomic surveillance system.

Due to the global nature of Covid-19 variants, the paper also suggests that the international community should also provide financial and technical support to bolster genomic surveillance in areas that are less resourced.

By following these public health measures, such as avoiding travel, incentivized isolation, wearing N95 masks and face shields, physical distancing, avoiding indoor activities, and implementing a comprehensive and coordinated genomic surveillance system we can avoid a potential rapid rise in cases stemming from the variants.