Hepatitis C is the leading cause of chronic liver disease and liver cancer in the world and affects an estimated 51 million people globally. Though the viral infection is easily diagnosable and treatable, a cure for hepatitis C remains elusive and one of the most prevalent public health issues in the United States and globally. In this series, we’ll explain what hepatitis C is and how it affects the body, as well as explore the barriers to curing hepatitis and propose new strategies to eliminate the disease.

Discovery

The existence of what we now know to be hepatitis C was first discovered in 1975 by a team of NIH researchers led by Dr. Stephen Feinstone. While developing new serological testing to diagnose post-transfusion hepatitis, Feinstone’s team found that many of their samples tested negative for both hepatitis A and hepatitis B, indicating that there was a new type of hepatitis caused by a novel infectious agent. This new, mysterious type of hepatitis was coined non-A, non-B hepatitis (NANBH) and was characterized by elevated liver transaminases closely associated with cirrhosis and liver disease. In 1978, Dr. Harvey J. Alter and his team at the NIH’s Department of Transfusion Medicine were able to confirm the serial infectious ability of this new virus by injecting blood samples from NANBH positive humans into chimpanzees, which have a similar genetic makeup to humans. By studying the infected chimpanzees, Alter’s team was able to understand the viral transmission of the new agent and learned that it was a small, enveloped virus. The identification of this new virus, however, proved difficult. The approaches used to identify the HAV and HBV viruses were unsuccessful in identifying HCV and necessitated the development of a new molecular cloning strategy. In 1985, George Kuo invented that cloning strategy by reverse transcribing mRNA from NANBH positive serum into cDNA. In 1989, a team at the Chiron Corporation led by Michael Houghton and Qui-Lim Choo were able to use that cDNA to successfully identify and replicate the virus. After publishing their findings, they named the new virus, the hepatitis C virus. HCV was then classified into the new genus of hepaciviruses in the family of Flaviviridae due to its similarities to the encephalitis flavivirus. In 2020 Dr. Alter and Haughton were awarded shares of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their part in discovering HCV.

Symptoms

Hepatitis C is a blood borne viral infection that affects the liver by causing inflammation and swelling of liver tissues. Acute infections are usually asymptomatic with only 20-30% of cases showing symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they present 2 weeks to 6 months after infection. Symptoms of an acute HCV infection can include jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), dark-colored urine, light-colored stools, fatigue, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, joint pain, and fever.

Approximately 80% of those with acute hepatitis C will go on to develop a next stage, chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis is slow progressing and is often asymptomatic for decades after infection. The long interval between infection and presentation of symptoms often prevents chronic hepatitis C from being diagnosed until extensive liver damage has already occurred. As a result, chronic hepatitis C symptoms include cirrhosis symptoms like ascites (accumulation of fluid and swelling of the abdominal cavity), spider angioma on the stomach, jaundice, and easy bruising and bleeding in addition to symptoms also associated with an acute infection.

Extrahepatic symptoms can also manifest. Chronic hepatitis C has been associated with skin rashes including palpable purpura and digital ulcerations, as well as neuralgia and impaired cognitive function. Low blood pressure, congestive heart failure, and difficulty regulating blood sugar have also been linked to chronic hepatitis C.

Immune Reactions

Acute HCV infection is easily detected in the body and readily triggers the body’s innate immune response. This first line defense against HCV employs the use of natural killer cells (NKs), proinflammatory cytokines, and the interferon-stimulated gene response (IGE) to fight the infection. The NKs and ISG responses work to interfere with HCV replication and kill off infected hepatocytes. While this swift, innate response is often not enough to curb the replication of HCV in liver tissue, it allows the body time to mount an adaptive immune response, a process that can take several weeks to months to develop. When the adaptive response starts taking effect, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells are released which play an important role in coordinating a sustained immune response and killing off infected cells.

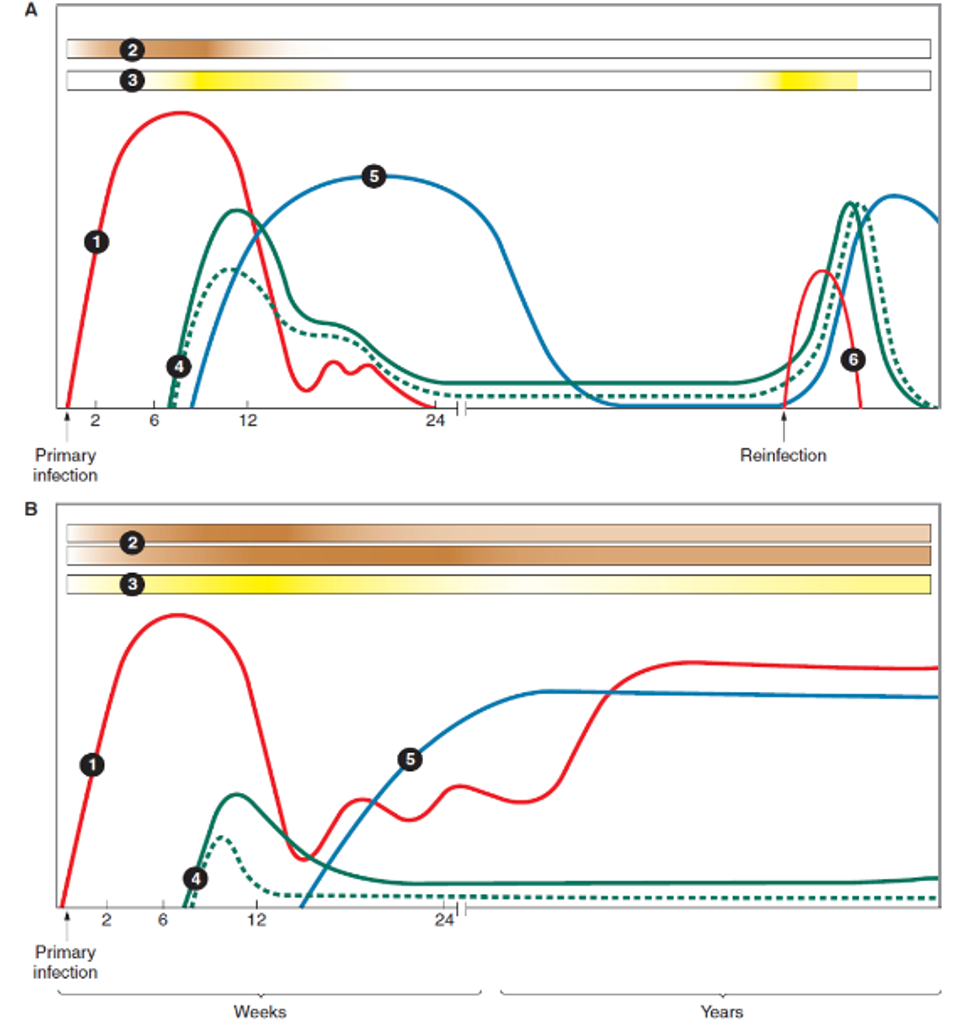

Immune reaction profile of (A) spontaneous clearance of HCV infection and (B) persistent HCV … [+]

FIELDS VIROLOGY

The profile and timing of the immune response to HCV can vary due to the capability of each body’s immune system and genetic makeup. In spontaneous clearance of HCV infection, the innate immune response displays high ISG activity within the first few days of infection. As the ISG response successfully stops replication of HCV, there is a sharp decline in viremia around 8-12 weeks after infection. This sharp decline is also associated with the rise of CD4+ and CD8+ cells as well as the release of B-cell derived neutralizing antibodies. As the infection clears, the adaptive immune system response declines but can rapidly reemerge with reinfection. Research shows that broadly employed, rapid, and persistent CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses are critical in HCV clearance. In cases where infection persists, the ISG response remains high but is unable to adequately control HCV replication. A strong ISG response that coincides with high, but stable viremia is characteristic of a chronic infection. In these cases, the release of CD4+ and CD+ T-cells is also delayed and less robust. These cells gradually exhaust and then disappear from blood circulation. The release of neutralizing antibodies is also delayed in chronic infections but they may persist longer than in spontaneous clearance cases.

Long Term Consequences

Natural history of hepatitis C infection

THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN COLLEGE OF GENERAL PRACTITIONERS