With thanksgiving in the rear-view window, the last thing most of us want to do is think about food, not to mention what those calories did to our waistlines. From deep-fried turkey to loaded mashed potatoes to freshly baked apple pie, there is no doubt that fat had a starring role at dinner tables across America. Now, in the sobering light of post-thanksgiving food comas, we continue our series on the science behind overeating.

In the first installment, we delved into Dr. David Kessler’s Bestseller, The End of Overeating, in which he frames fat, sugar, and salt as the main driver behind overeating. The food industry, as he argues, profits from the dissonance between logical restraint and a carnal drive to continue eating beyond the point of satiation. The second and most recent installment explored the genetic influences that predispose some people to being thin, regardless of exercise, diet, and other lifestyle factors. Genetics, however, are not destiny. For that reason, this installment will consider what actually happens when you consume high calorie foods.

Fat, sugar, and salt contribute significantly to our daily calorie intake. There is something about fat, in particular, that makes us continue to crave it even after the point of feeling full. If you have ever had deep-fried onion rings or a plate full of French fries, the craving for more is not merely driven by taste. It is how these foods smell and feel in our mouths. It is how after just one taste you cannot help but devour the entire plate. In a recent paper published in Nature, investigators at Columbia University argue that restricting fat cravings may be outside our conscious control. The results of their experiments found that fat activates a post-ingestion gut-brain circuit that keeps us wanting more.

Li et al. began their investigation by presenting their mice subjects with a choice between two drinking solutions, one sweetened with artificial sweeteners and the other saturated with fat. Presented with both options at the same time, the animals had an immediate preference for the artificially sweetened drink. Within 24 hours, however, their preferences considerably shifted to the extent that, by the 48 hours, the mice almost exclusively drank from the fat mixture. The animals appeared to have developed a strong appetite for fat over the sweet drink with an equal number of calories. Investigators concluded that there may be something unique about how fat interacts with the gut that allows it to influence our behavior.

Activation of sweet taste receptors generated the initial preference for the artificial sweetener, but as the animals consumed more of the fat infused drink, it became clear to researchers that there may be a post-ingestion circuit sending signals to the brain. To be sure that this behavioral shift had nothing to do with taste, Li et al. genetically engineered mice without fat-activated taste receptors. Despite being blinded to its taste, the animals continued to exhibit a higher preference for fat, compared to the artificial sweeteners.

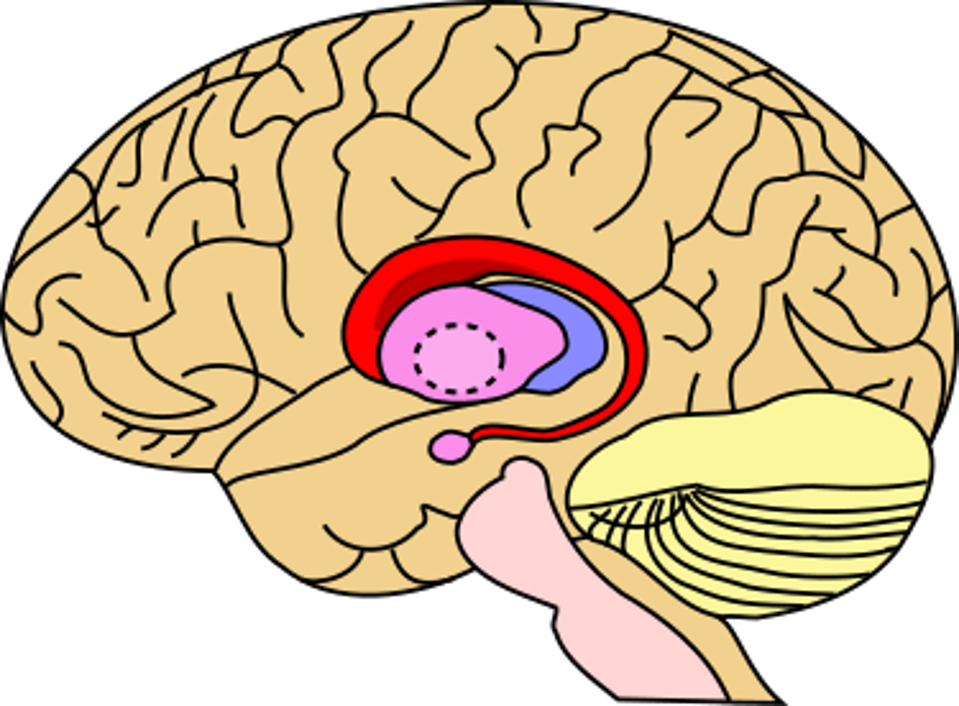

While the mice ate, investigators observed an interesting pattern of neural activity in the brain. By placing electrodes on the animal’s heads, they were able to record what was happening in the brain while they ate different types of fat, compared to a texture matched non-fat drink. Only the fat-saturated drink mixtures were able to activate a particular part of the brain called the caudate nucleus, located deep within the brainstem. Caudate nucleus and other parts of the brainstem serve as keep connectors between the brain and the rest of the body.

Figure: Illustration of the caudate nucleus in red. WIKIPEDIA COMMONS/ LEEVANJACKSON

In addition to its well understood role in movement, emerging studies suggest that the caudate nucleus plays a critical role in associative learning and reward-driven behaviors. This is also the part of the brain that has been shown to influence appetite and digestion via the gut-brain axis. Eating your favorite food tastes good because neurons in this brain region release dopamine neurotransmitters that teach your brain to associate that particular food with a good feeling.

What connects the gut to the brain? As the longest cranial nerve, the vagus nerve stretches from the caudate nucleus and branches down the neck and torso. This is the superhighway that connects the brain to all your vital organs, including the gut’s digestive system. For example, while your body is at rest, the brain signals down the vagus nerve to lower your heart rate and slow your breathing in order to expend more energy digesting and extracting nutrients.

If the brain can send down signals to increase food intake through this nerve, Li et al. hypothesized that fat-activated receptors in the gut can also influence how the brain responds to certain foods. For their next set of experiments, rather than allowing the animals to drink the solution, Li et. al inserted a feeding tube directly into the gut. What they observed not only reinforced the existence of a gut-brain circuit, but also called attention to the role of the caudate nucleus within this pathway. In fact, when investigators exposed these neurons to pharmacological blockers the prevented them from receiving signals from the vagus nerve, the mice no longer developed a strong preference for fat, regardless of how many times they were exposed to the fat infusions. The animals, however, still exhibited an initial preference for the artificial sweetener.

To confirm these findings, Li et al. hoped to find that severing the vagus nerve disrupted the gut-brain axis. Just as they thought, cutting the vagus nerve effectively prevented the mice from developing fat preferences, as well as eliminated any gut-linked neural activity in the caudal nucleus. If the gut and the brain talk, the vagus nerve, as the main model of communication, may be a likely pharmacological target for treating obesity.

Conclusion

America has a fat problem. The USDA recommends that fats should only make up 30% of your calories for a day. Having too much fat in your diet, especially high-processed saturated fats, can lead to significant health problems, including high cholesterol and obesity. For someone who eats 2,000 calories, up to 66 g of fat should be consumed per day. Thanks to the food industry’s efforts to incorporate fat into as many foods and drinks as possible, many Americans eat much more than that.

In a world where fat is added to nearly every meal, the challenge many Americans face is how to cap their daily fat intake. Many of the foods and drinks found on supermarket shelves and restaurant menus are infused with considerable amounts of fats that taste good, albeit terrible for our bodies. In Dr. Kessler’s book, The End of Overeating, he describes how the food industry attracts and hijacks all our senses through food science and skillful marketing. Li et al. now argues that we are biologically wired to crave fat. Eating food rich in fat triggers a deep seeded signal that takes tremendous willpower to override. Although we cannot completely get rid of the vagus nerve, this study offers the insight that one day the insatiable desire for high fat foods could be medically treated.