In the span of last weekend alone, more than 80,000 new cases of Covid-19 were reported across the United States. Worse, the disease claims the lives of about 1,000 Americans daily. Meanwhile in China, the country where it all began, the number of cases from the past week didn’t even reach 200. The amount of deaths per day? On average, one to two.

These numbers tell a tale of two countries in which initial response to the pandemic was as different as night and day—as was its impact on the lives of citizens. In China, crisis struck hard and fast, but gave way to rigorous measures of suppression and control that still hold steady. By contrast, the only stability to be found in the United States today lies in the steady increase of outbreaks, fatalities, and general chaos, all of which shows no sign of stopping.

There is a strategy for containing Covid-19 that would bring an end to the pandemic in the United States without a vaccine or drug therapy. It is cost-effective, compatible with American values, and needs only two to three months to take effect. It uses the latest science to tailor one of the most effective components of China’s pandemic response—assisted isolation—to the sweeping scale of the U.S. outbreaks, and it deploys the latest testing technology to bring rapid diagnostics into the homes of hundreds of millions of Americans.

While it will be some time before China is rid of Covid-19 completely, for a nation of nearly 1.4 billion people it has come incredibly close. Their pandemic response, which the World Health Organization (WHO) called “perhaps the most ambitious, agile, and aggressive disease containment effort in history,” continues to evolve in response to new challenges. In this article, I compare the containment strategies of China and the United States and explain how we can put an American spin to achieve the same degree of success. Rather than mandatory isolation and contact tracing, we can use home testing and assisted isolation to put an end to this crisis.

China’s containment strategy

Most Americans, according to data collected by the Pew Research Center, believe China is in no small part to blame for the magnitude of the crisis and the devastation it has wrought. Some greet empirical and photographic evidence of China’s return to “normal” with deep and conspiratorial suspicion. As the Chair and President of an international think tank with offices in Shanghai and Beijing, I know such accusations couldn’t be further from the truth. My Chinese colleagues frequent movie theaters, public performances, and restaurants. They send their children to school and travel the country freely to visit relatives and friends. No longer do they live in fear.

When early reports of a “mystery pneumonia-like illness” first surfaced in Wuhan in early December, local authorities made the fatal mistake of trying to obscure evidence and censor whistleblowers rather than notify the central government. But when national leadership in Beijing received word, they acted swiftly, alerting the WHO on December 31. China had made enormous strides in its public health and biomedical research capabilities since SARS, the first novel coronavirus pandemic that killed hundreds in 2002. While SARS ultimately didn’t reach nearly as many people as Covid-19, it did lead to considerable economic damage.

From January 1 onwards, communication with international health agencies like the WHO became clear and consistent. Researchers mobilized and began investigating the disease with haste, identifying the virus on January 7 and releasing its entire genomic sequence to the world just three days later. Within two weeks, Wuhan and 15 surrounding cities in the Hubei province had entered lockdown—bringing the social and economic life of 60 million people to a screeching halt. Many hubs and modes of intercity transport were suspended, as were the crowd-drawing festivals that normally prompt huge shifts in population flow each spring. When the streets emptied out but local hospitals began to overflow, massive temporary shelter hospitals were constructed with the sole purpose of treating Covid-19 patients.

These large-scale directives, which came from the top down, ultimately served one common purpose: find the virus and drive it out at all costs. To detect cases as early and often as possible, temperature screenings and testing checkpoints were installed along streets, outside shops and markets, and around the exits and entrances of bus and train stations. Hotels were repurposed as quarantine facilities that hosted international travelers and others suspected of exposure—for free at first, but later at a cost to deter incoming visits. Anyone confirmed to have Covid-19 was rapidly contact traced and their close contacts quarantined, ideally within 24 to 48 hours. A high-tech Health Code system monitored the symptoms and movements of those identified, alerting local health authorities whenever someone infected or exposed broke isolation or quarantine. A green health code indicates good health; a yellow code, exposure; and a red code, infection. To this day, a green health code is still required to enter some establishments.

After a month, towards the end of February, the number of Covid-19 cases in China began a steady decline. On April 8, the lockdown and travel restrictions in Wuhan lifted. All culminated in mid-May when China, for the first time since January, reported zero new cases of Covid-19. Since then, flare-ups or so-called “second waves” have been met with the blunt force of testing—an instrument of disease control that hasn’t received nearly as much attention as vaccines or drug treatments, but is perhaps the most effective means we have at our disposal for stopping the spread of Covid-19 in its tracks.

United States containment strategy

In terms of the leadership and actions of the national government, the United States and China couldn’t be more different. U.S. medical intelligence officials received word of a “cataclysmic” disease emerging in Wuhan as early as November 2019, and by January 20 the first case of Covid-19 on American shores was identified in Seattle, Washington. Despite this, the Trump administration didn’t declare the pandemic to be a national emergency, place bulk orders on medical supplies, or issue safety guidelines until mid-March. Even then the restrictions were merely recommended, not mandated—a stance so lenient and ineffectual that several states didn’t enact limitations of any kind for months. California became the first to issue a stay-at-home order on March 19, followed swiftly by Nevada, Illinois, New Jersey, and Louisiana. A similar order took effect in New York on March 22—the same day New York City was declared a new global epicenter of the pandemic.

In China, many neighborhoods and compounds in Wuhan and beyond banded together to carry out the orders given out by central leadership, appointing community representatives who could help local authorities monitor the health of residents. In the United States, inconsistent messaging from the White House on everything from drug treatments to mask-wearing appeared to have the opposite effect. When the federal “Guidelines for Opening Up American Again” were released on April 16, it fell on individual businesses, institutions, and above all citizens to reconcile conflicting sources of information and make decisions accordingly. State and local governments enforced and discarded Covid-19 protections in piecemeal fashion, such that even those who followed every possible precaution remained vulnerable to transmission.

On April 28, Covid-19 cases in the United States topped one million. Today, four months later, that number is now over six million. With schools reopening and child infections on the rise, the demand for a robust, unifying, and evidence-based containment strategy is greater than ever—especially now that our fears around the possibility of Covid-19 reinfection seem to be coming true. We can either learn and adapt China’s success for our own purposes, or allow a mess of our own making to all but overwhelm us.

Retooling our response

The new 15-minute test created by Abbott Laboratories. Credit: Abbott Laboratories

Abbott’s BinaxNOW™ COVID-19 Ag Card is highly portable, about the size of a credit card, and doesn’t require added equipment.

In lieu of a nationwide shutdown that makes it easier to constrict mobility and subdue contagion, a combination of home testing and assisted isolation can give local and national authorities the information they need to understand and reduce the scope of an outbreak. If the key to containment in China was surveillance and constraint, the American counterpart might be convenience and affordability—using federal command and funding to pump 50 t0 100 million tests into the homes of Americans each or every other day.

An antigen test fast enough to make this vision a reality was authorized for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 26. Created by Abbott Laboratories, the rapid antigen test has a price tag of just $5 a pop and can deliver results within 15 minutes. What we really need, however, is a saliva-based test, which unlike nasopharyngeal swabs requires no intervention from healthcare workers. This technology, which isn’t yet available but will be soon, would make Covid-19 tests as convenient and easy for families to use as pregnancy tests.

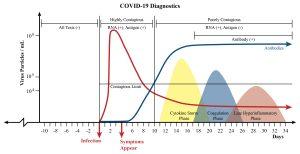

If the overarching goal of China’s pandemic response was to isolate those exposed to the virus rather than those already infected, the criteria for isolation in the United States might be contagiousness instead. Data from preprint studies shows that the concentration of the Covid-19 virus in our nasal passages and throat is at its highest from before symptoms even appear to three or four days after they do (see Figure 1). That means the earliest phase of infection, when 10^6 to 10^9 viral particles are swarming our airways, is when we’re most likely to pass the virus on to others—as well as a critical juncture for testing and isolation.

PCR tests, which detect viral DNA, are normally preferred to antigen tests like Abbott’s due to their heightened sensitivity to the virus. But when we test people early enough, the concentration of the virus in our bodies is so great that a sensitive test isn’t needed (see Figure 1). Isolating individuals when they’re at their most contagious also prevents them from exposing—and potentially infecting—the many people they may come into contact with. If rapid tests are made widely available for a low enough cost, the possibility of picking up on infection at this stage becomes more feasible. So does the objective of testing people every couple days or even daily.

Figure 1. A chart that overlays the disease progression for Covid-19 with information on diagnostics and contagiousness.

The next step is assisted isolation. Children who test positive for the disease would isolate with their families at home, where health authorities can monitor their disease progression and volunteers can deliver food and medical supplies. Adults 18 and older who don’t live alone would isolate in a hotel room or hospital, depending on their condition, where they could also be monitored and cared for. To ensure that data on their health status ends up in the right hands, lawmakers could create legislation—as political committees in California did back in August—that requires Covid-19 cases to be reported within 24 hours of detection. While the California bill applied to employers only, with home tests mandatory reporting could be extended to the population at large. This would all but eliminate the need for contact tracing, which served a critical purpose in China but has so far been poorly organized in ineffective in most parts of the United States.

The White House, after months of inaction, took the first major step towards advancing such a strategy in August when it put in a mass order of 150 million Abbott rapid antigen tests. Though the biggest investment the federal government has made in testing to date, it still isn’t nearly enough. We need many more hundreds of millions—billions, even—of tests to ensure equitable access to cheap and rapid home testing across the United States. Two years ago in Egypt, another rapid test made by Abbott Laboratories was used to screen the majority of adult Egyptians for hepatitis C for only 50 cents each. Back in May, China was able to test nine million people in Wuhan for Covid-19—keeping a second wave at bay as a result. If the United States is to contain its epidemic anytime soon, we must find a way to take what countries have successfully done before and retool it for our own purposes. Otherwise, we will continue to be exceptional only insofar as how staggeringly we have failed.