At this pivotal juncture in our nation’s history, California has become a microcosm of broader developments taking shape across the US.

The country’s most populous state is also its most diverse, home to a wide range of cultures, ethnicities, and economies. To the north lie counties that voted red in the 2020 election and share more sensibilities with Dakotans than Los Angelenos. To the south, the US-Mexico border where millions of immigrants have passed through at rates comparable to Texas. And down the middle, the abundantly verdant, 450-mile Central Valley, where 40 billion pounds of milk, two thirds of the nation’s fruits and nuts, and a third of its vegetables are produced each year.

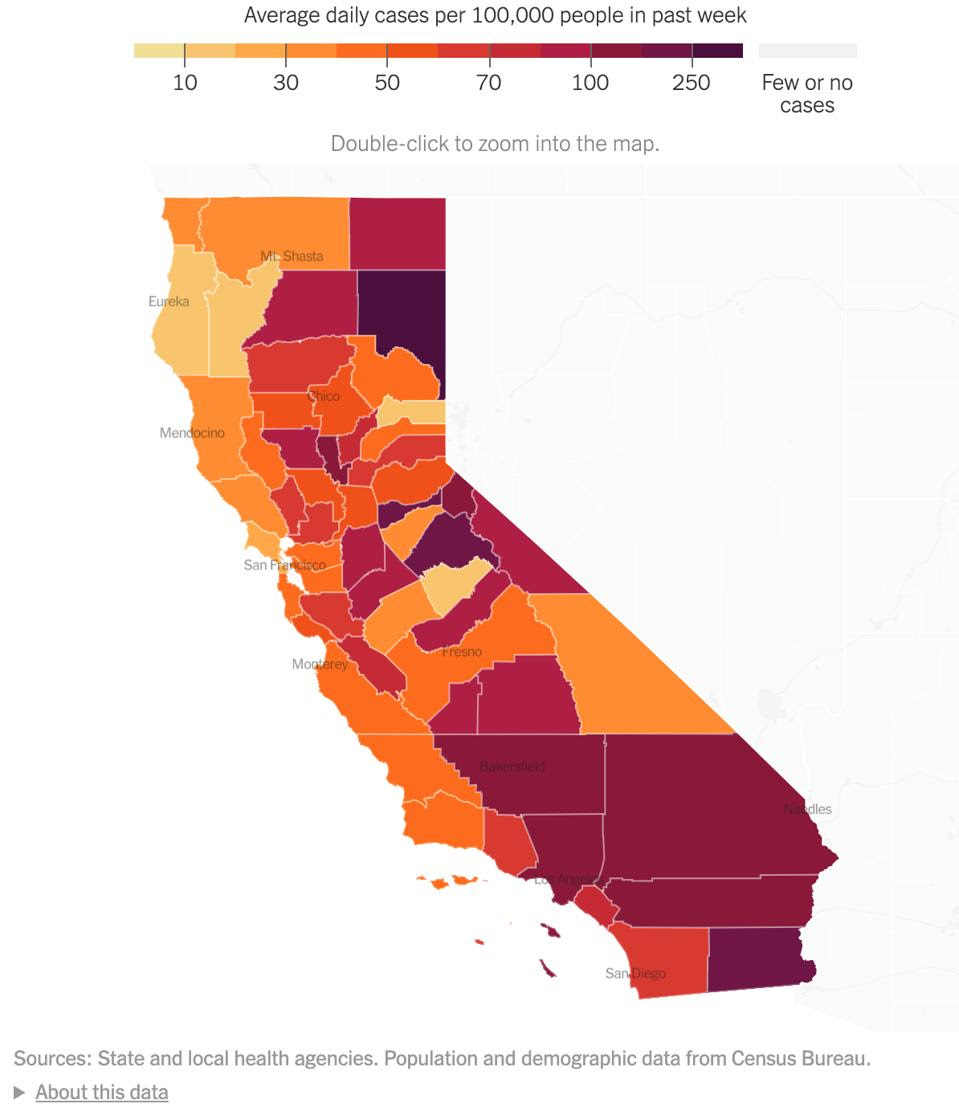

All three regions are critical to Californian history and identity. All three are being hit hard by Covid-19.

Statewide, case counts have increased by nearly 120 percent and deaths about 160 percent in just two weeks. Per California’s latest round of Covid-19 restrictions, a stay-at-home order kicks in wherever ICU capacity—namely, the share of unoccupied beds in intensive care units—dips below 15 percent, a milestone that Sacramento and Southern California have already reached. In San Joaquin County, a mostly rural region in the middle of Central Valley, zero ICU beds were available as of last Saturday. Even San Francisco is expected to run out by the end of December. As Dr. Eyad Almasri, a pulmonologist who works in Fresno, told the Los Angeles Times, “We’re saving lives. We just can’t save everyone at once.”

A map depicting the average daily cases per 100,000 people in the past week in California. Source: … [+]THE NEW YORK TIMES

While hospitalized Covid-19 patients are all shapes and ages, some populations carry a share of the disease burden disproportionate to their actual size. In California, the millions who labor in the state’s farms, meatpacking plants, and other food processing facilities—countless of them migrant workers of color—are exposed to Covid-19 at rates far higher than those who can either work comfortably from home or, as Tesla CEO Elon Musk did days ago, comfortably relocate. In the fields and factories where social distancing, frequent handwashing, and other safety guidelines are difficult to enforce, and in the crowded households and dormitory-style complexes where many migrant workers live, the virus has considerably more room to grow. And because this virus isn’t one to discriminate between viable human hosts, outbreaks that occur under poor working conditions will find a way to spread into the cities, suburbs, and beyond.

In the rural north, the situation isn’t much better. Lassen County, where more Covid-19 cases per 100,000 have been confirmed in the past week than anywhere else in the state, is struggling to contain an ongoing outbreak at High Desert State Prison, where active cases currently outnumber those in local communities. About a fifth of the prison’s population has tested positive for Covid-19, as have 160 staff members. Given that Lassen County also has the designation of being the “Trumpiest county” in California, meaning residents voted for Trump by the widest margin in this year’s presidential election, public health measures like mask-wearing likely aren’t so popular. Rural communities in general also have higher incidences of chronic illness, smoking, obesity, and other adverse health conditions that increase susceptibility to severe Covid-19, not to mention far less doctors and critical care facilities than urban areas.

Now that the winter holidays are upon us—and with them, a precipitous increase in travel and indoor gatherings—the patchwork of public health protocols that kept case counts relatively low in the fall will only continue to prove insufficient. The 325,000 doses of Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine that California received this week may help, but the jury is still out on whether it prevents the spread of disease. Especially since California has fewer ICU beds per capita than most states, what the state needs as it awaits more vaccines are more robust, targeted, and comprehensive public health interventions that provide assistance to those who need it most. The idea isn’t to force people to comply with stay-at-home orders and other restrictions, but make the choice that much easier.

This month, health officials in Santa Clara County launched a door-to-door testing program in the neighborhood of East San Jose, where more than half of residents are Latino. Bilingual volunteers will distribute self-administered home tests to anyone who needs them, but with particular consideration Latino communities who may not have the means to get tested themselves. The California Department of Food and Agriculture is also expanding its Housing for Harvest program, an initiative to provide vulnerable agricultural and food processing workers with temporary housing options if they’re sick and need to self-isolate. In addition to securing a hotel room for the duration of their quarantine, participants also receive meals, wellness checks, and if needed economic assistance for family members at home. The program, introduced by Governor Gavin Newsom in July, now has footholds in San Joaquin, Fresno, and other Central Valley counties.

Now more than ever, even with a vaccine on hand, Covid-19 is spiraling out of control in the US. To contain it, we need lockdowns as drastic as those imposed in France and across Europe. But we also need public health interventions that bring support to people who have difficulty accessing it on their own. They must be widespread and, for recipients, either low-cost or completely free. Some individuals will no doubt choose to defy public health guidelines willingly. As California Senator Richard Pan put it to the Los Angeles Times, “We can’t save people from themselves after a certain point.” But those we can help, we should. Simple as that.