The party on Friday was a blast except for one thing: you think you caught Covid. Saturday you felt fine, but you realize that the runny nose and cough you developed Sunday afternoon may not be so innocent. One of your roommates returns from work Monday morning with a rapid antigen test for you to use, and turns out the suspicion is true. You suppose you should isolate, but for how long? Until you feel better? Should you just wait for five days and assume all is well? And what day would you even count from? From Friday, the start of the party; Sunday, the day the coughing began; or maybe Monday, when the antigen test came back positive?

Most of us are concerned about how long we should isolate for when Covid positive. Current guidelines set by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and the US’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest a baseline of five days. These policies developed in response to the urgent need for healthcare and essential workers to return to their positions as soon as possible, regardless if some fraction would remain contagious. A new study published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine applies real-world data to answer the questions of how and when to safely leave Covid-19 isolation. The team discovers, in particular, that the fixed-date recommendation releases a significant number of people from self-isolation who are likely still infectious, and that the best practice is to test out of isolation with rapid antigen tests.

Natural Covid-19 infection study

In this study, Hakki et al. analyzed the infectious period of SARS-CoV-2 in a real-world community setting over several months. Enrollment occurred twice, once between September 2020 and March 2021, and once between May 2021 and October 2021. The involved household and non-household contacts had mild cases of Covid-19, all confirmed through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

The participants filled out a daily diary of symptoms and were considered symptomatic if they experienced one of three hallmark Covid-19 symptoms prior to Omicron—fever, cough or loss/change in smell or taste—or at least two of the following symptoms: muscle aches, headache, appetite loss, sore throat.

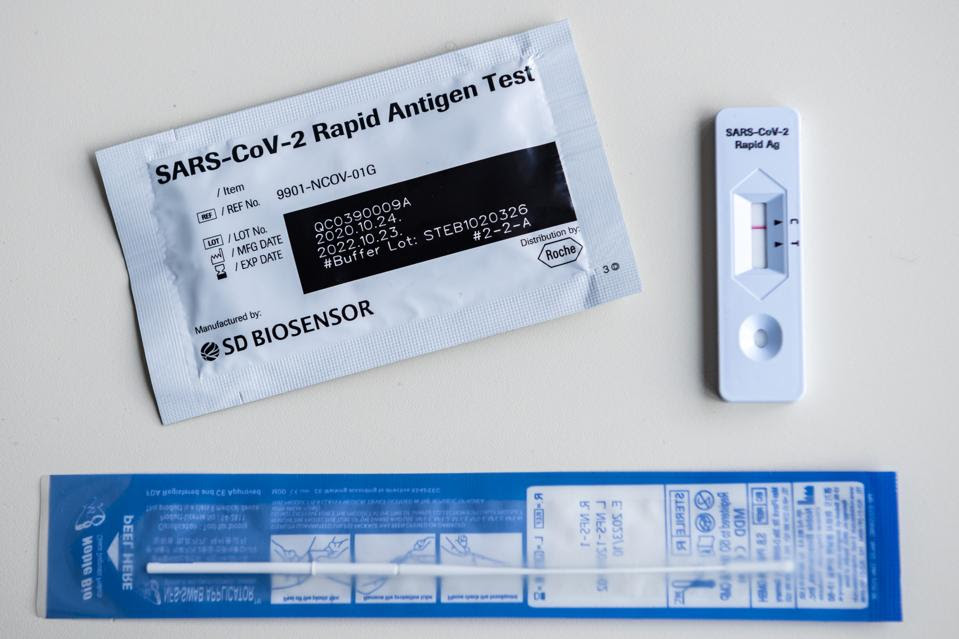

The team tracked the viral RNA load, or the amount of virus detectable in an infected individual, for the duration of the illness through daily reverse transcription PCR tests (RT-PCR). Plaque assays measured the level of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in samples. The participants also performed self-administered Covid-19 lateral flow tests—otherwise known as rapid antigen tests—throughout. This information, when paired with the RT-PCR results, helped determine how effective Covid-19 antigen tests are at detecting SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins.

A photo of a lateral flow test, otherwise known as a rapid antigen test. Using a nasal swab sample, the test detects whether or not anti-SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins are present in the body. Unlike with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, the results appear quickly and directly on the testing apparatus. (Photo by JENS SCHLUETER / AFP) (Photo by JENS SCHLUETER/AFP via Getty Images) AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Study Results

The investigators narrowed the cohort size to those with positive PCR results and a detectable viral growth phase (an observed low initial viral load followed by an increase). A total of 57 cases were analyzed. This number was further reduced to a cohort of 38 who had a definitive symptom-onset date and shed culturable virus within the sampling period. The group had mixed vaccination status, but there were no significant differences in demographics between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. Most participants were white, middle aged (between 29-49 years old), and of a healthy BMI.

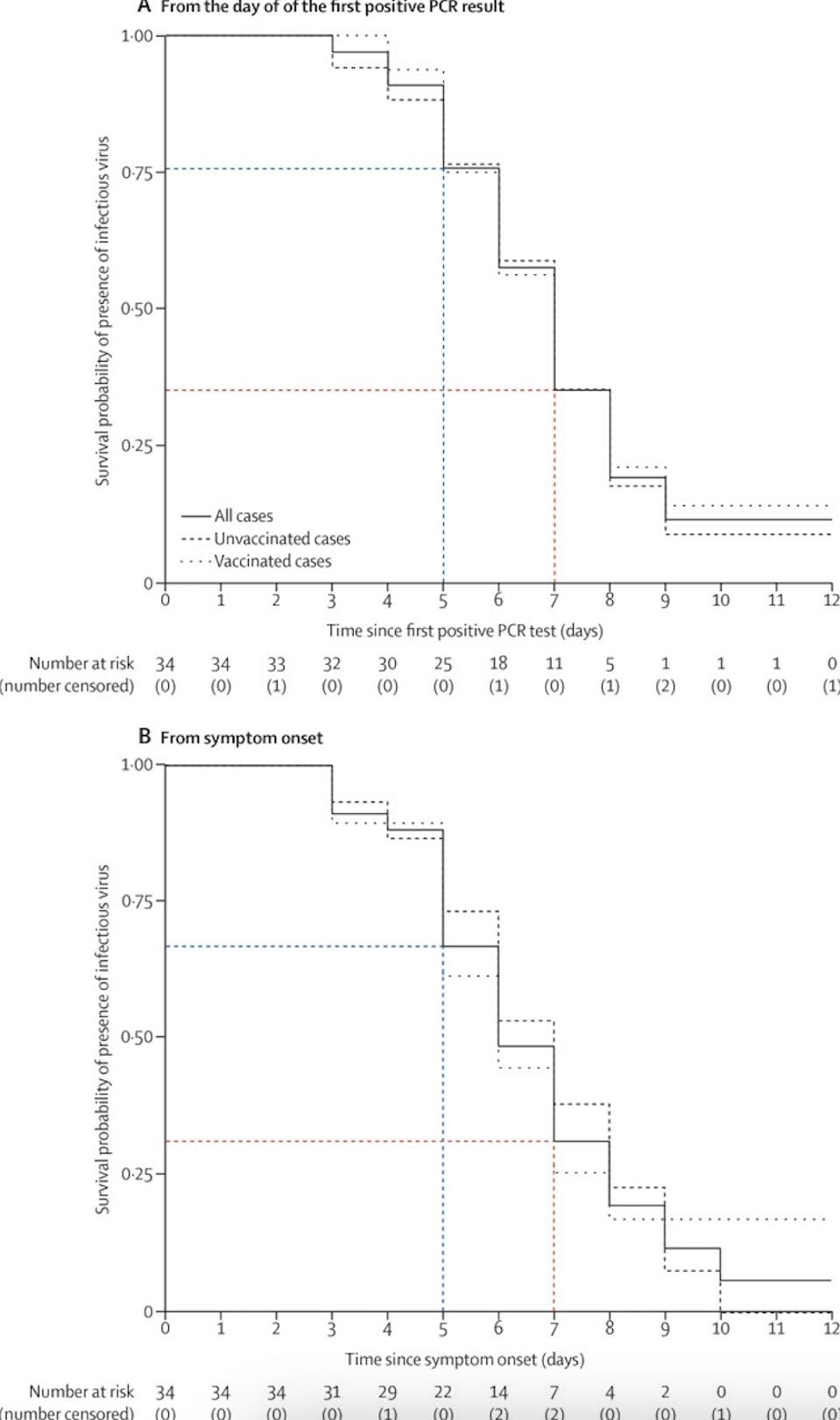

Figure 1: The survival probability of infectious virus presence, as determined by plaque assays. When analyzed from first positive PCR result and from symptom onset, it is clear that infectious virus survives well within the first five days (in blue); after five days, the probability of survival drops off, but is still significant, especially six and seven days (in red) after positive PCR result/symptom onset. HAKKI ET AL.

Very few people—only 20% of cases (7 out of 35 participants)—shed infectious virus before developing symptoms. On average, infectiousness peaked three days after symptom onset. These levels decreased over the course of the illness; figure 1 illustrates this decline well by graphing the chances for infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus to survive in the body based on symptom onset and first positive PCR result. By Day 5, however, about 62% of the cohort (22 of 34 cases) still continued to shed infectious virus. By Day 7, 23% of the cohort (8 of 34 cases) still shed infectious virus. If someone with Covid-19 leaves isolation after five days, as mentioned in NHS guidelines, likely this person would continue to be infectious. This could be especially ill advised if there are people at home who are highly at risk for Covid-19.

Hakki et al. also investigated the efficacy of lateral flow tests. The sensitivity of rapid antigen tests was found to be poor at the start of illness but high after peak infectious levels (67% versus 92%). Given this finding, the researchers suggest that rapid antigen tests are unreliable for early diagnosis of Covid-19 but useful for testing out of isolation.

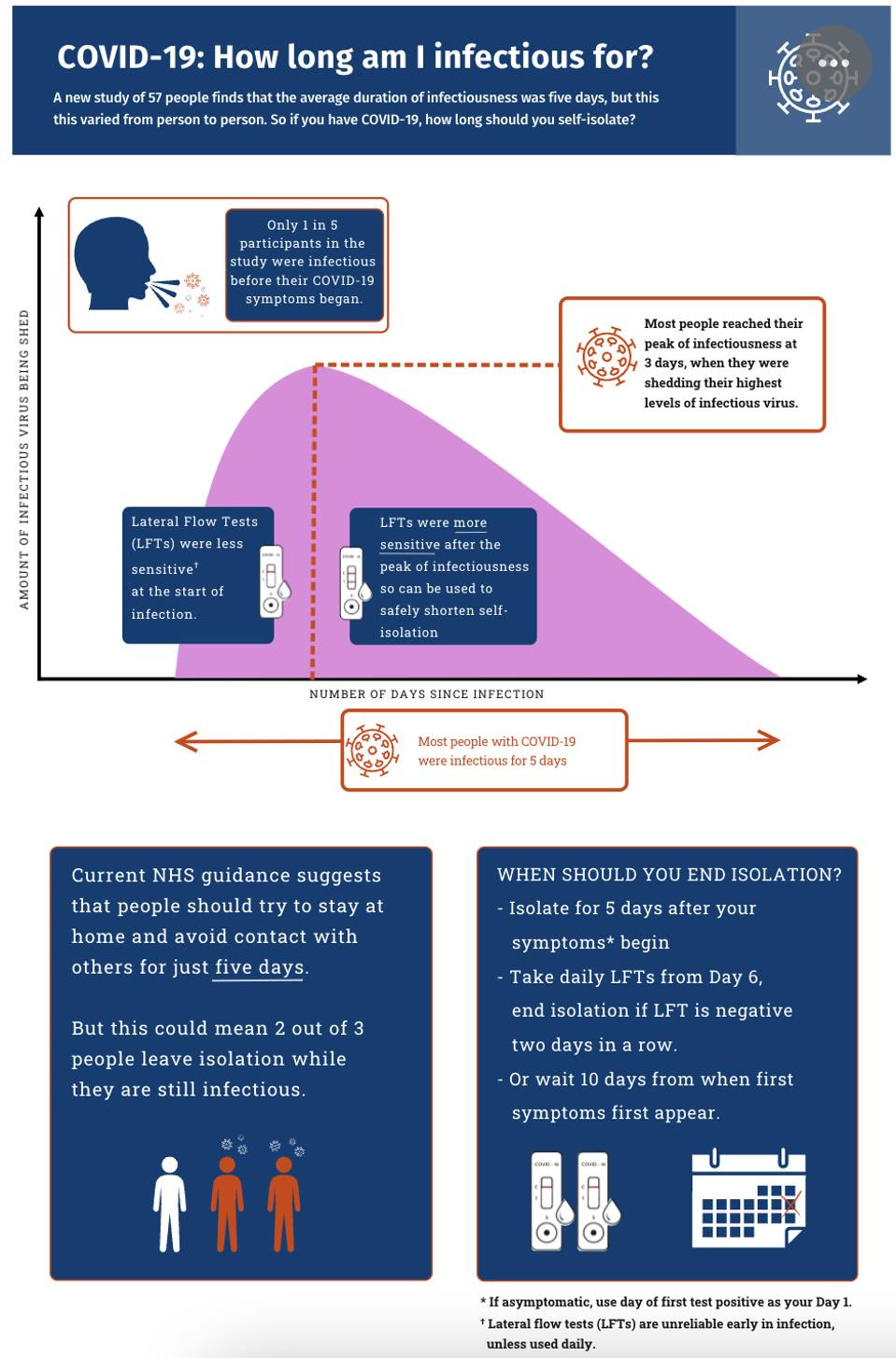

Figure 2: A graphical summary of the study’s results by the Imperial College London. Based on study results, it is ill advised to assume that infectiousness ends after five days of Covid-19 sickness. To best decide when to leave isolation, a daily rapid test should be taken after Day 5. If the results come back negative two days in a row, it is safe to leave isolation. IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON Link Added

So, how long should you isolate for?

Although the CDC recommends that isolation end for people with symptomatic Covid-19 at Day 5 if fever free for 24 hours or if symptoms improve, recent data suggests that this may be unwise.

According to this study by the Imperial College London, self-isolation should begin once symptoms begin. Day 0 represents the first day symptoms appeared—rather than when the positive test came back—and Day 1 would be a full day afterwards. In the best case scenario, suspicions of Covid-19 would be confirmed with a PCR test rather than a rapid antigen test, which appears to be less effective around symptom onset. Most people will still be infectious at Day 5, albeit much less so than originally. To leave isolation after the fifth day, the researchers suggest using a rapid antigen test once a day; if the test returns negative two days in a row, it should be fine to resume social activities (see summary in Figure 2). This contrasts CDC recommendations which use testing to determine when to stop wearing masks after isolation ends on Day 5.

This guidance is based on cohorts sick with Pre-alpha, Alpha and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2. The omicron variants now in circulation—predominantly variants BA.5, followed by BA.4.5 and BA.4—seem to have lower viral loads and shed for less time than the variants in the study. Although this may suggest that Omicron variants are less infectious, these protocols still apply to those wishing to safely exit isolation.

Testing out of isolation diminishes the chances of spreading Covid-19 to loved ones. Using a fixed date, in contrast, can be particularly disadvantageous for those in households with people at risk of Covid-19 and for people taking Paxlovid, a Covid-19 antiviral. The most recent example of this risk is President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden, who experienced a relapse in symptoms due to Paxlovid rebound and had to extend their isolation.

At the end of the day, the best course of action would be to prepare for the worse. Prevent infection to begin with by wearing a mask in crowded locations. If possible, get vaccinated and boosted to reduce the odds of developing severe Covid-19. And lastly, store a couple of unexpired rapid antigen tests at home so that, should symptoms arise, it can be easy to know when to safely leave isolation.