Here we describe the use of CAR T therapy to treat multiple sclerosis in mice. Previous installments discuss the fundamentals of CAR T and its applications for B cell cancers, multiple myeloma, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and the heart, as well as use of antibody switches to control CAR T cell activation and new research on combination CRISPR/CAR T therapy.

A study of mice by the researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine suggests that CAR T therapy offers a new opportunity to treat and possibly cure multiple sclerosis.

Around 1 million people in the United States have this autoimmune disease. The symptoms that arise—numbness, double vision, and tremor among others—impact the brain and nerves, and can potentially disable. Available treatment options only patch the problem and do not cure it. CAR T therapy may help piece together some missing clues. While the therapeutic is best known for its uses against cancer, it has shown recent promise to treat other autoimmune diseases including lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Here, the researchers extend this potential to multiple sclerosis in their animal model of the disease—a hopeful step towards eventual success in humans.

What is Multiple Sclerosis?

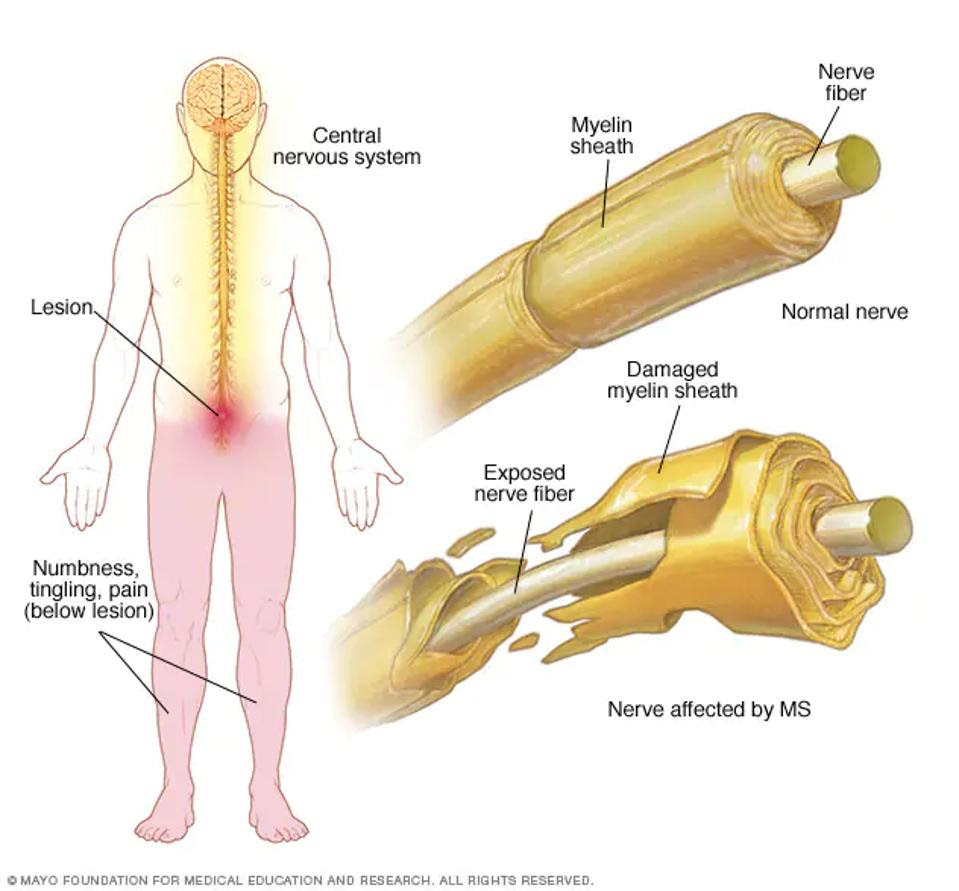

Multiple sclerosis (MS) occurs when the immune system wrongfully perceives the body’s own cells as a threat. White blood cells called helper T cells or CD4+ cells go rogue and target the outer covering of the nerves. This covering, similar to insulation on wires, protects the nerve fiber inside (see Figure 1). When damaged, the nerves cannot properly send electrical signals to other parts of the body and thus impedes communication between the brain, spinal cord and other parts of the body.

The degradation of the nerve sheath, otherwise known as demyelination, manifests signs variably from person to person. Multiple sclerosis-related nerve damage commonly causes numbness and tingling, fatigue or impaired vision among other symptoms. Although treatment options such as steroids or physical therapy can ease MS flare-ups and relapses, a cure has yet to surface.

FIGURE 1: With multiple sclerosis, the immune system targets the outer sheath covering the nerve and exposes the nerve fiber. This can cause a range of symptoms including numbness, tingling and pain.

MAYO FOUNDATION FOR MEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

CAR T Cells Target Autoimmunity

A recent study published in Science Immunology builds towards a possible cure for multiple sclerosis by using CAR T Therapy. The therapy relies on Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells to detect and destroy malignant cells inside the patient’s body.

To create CAR T cells, scientists attach new receptors onto a patient’s extracted killer T cells—usually this meshes the detection power of an antibody onto killer T cell machinery. The CAR T cell, once reinfused into the body, possesses a heightened ability to recognize and destroy cells with a specific biological tag, otherwise known as an antigen.

This CAR T design has proven effective against cancer, but cannot be applied to autoimmunity without first changing the chimeric antigen receptor. Instead of targeting antigens on the surface of cancer cells, the CAR T cell must now target the self-reactive helper T cells which perpetuate the autoimmune disease.

CAR T Cell Design for Multiple Sclerosis

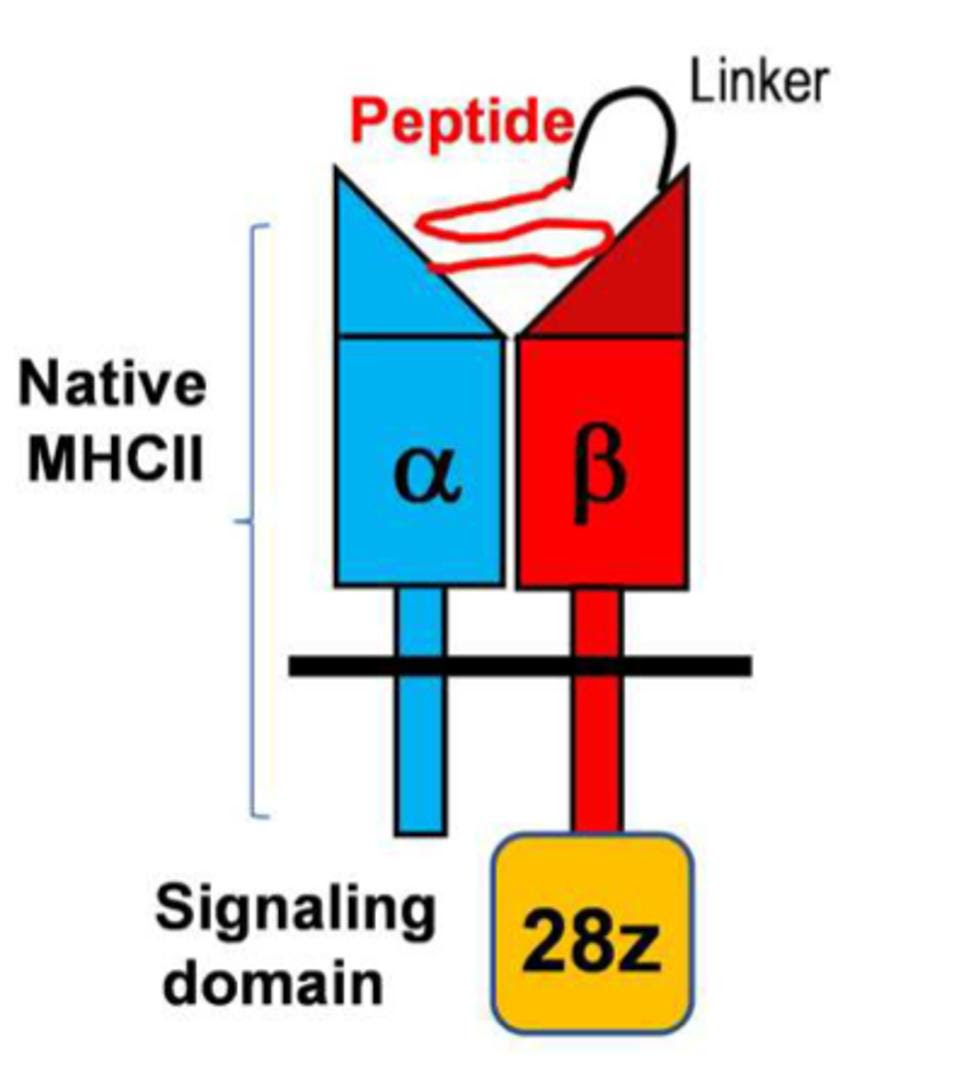

For this study, the researchers created a chimeric antigen receptor which can bind to MS-related helper T cell receptors in mice. The signaling molecules remained the same as usual. However, a protein complex replaced the oft-seen antibody-derived antigen detection region.

Figure 2 illustrates this design. It utilizes a major histocompatibility class II (MHC II) molecule, a structure not found on killer T cells, alongside a peptide attached by a flexible linker. The team found that they could easily change the presentation—and thus the targeting—of this protein complex, pointing to the adaptable nature of the design. They programmed the CAR T cells to initially target MOG, a protein found on the surface of myelin that pathogenic helper T cells react to in mice models of multiple sclerosis.

FIGURE 2: Schematic of a peptide/major histocompatibility class II chimeric antigen receptor (pMHC II CAR). The signaling domain consists of a CD3ζ molecule and a CD28 costimulatory molecule. The pMHC II domain can be changed and personalized depending on the desired allele.

YI ET AL.

Success for CAR T Therapy

The researchers tested the efficiency of this design in several stages. They first confirmed that the basic CAR T cell design seen in Figure 2 could target helper T cells with specific receptors in mice. Even without standard practices such as lymphodepletion, the CAR T cells eliminated almost all of the T cells they were programmed to target.

The therapy only found partial success in mice induced with an autoimmune disease to mimic multiple sclerosis in humans. The CAR T cells did not efficiently eliminate their first target: 2D2 T cells known for inducing multiple sclerosis in animals. The authors surmised that, due to low-affinity between these harmful helper T cells and the MOG CAR T cells, the cells fail to bind strongly to each other and thus influences the response.

Fascinatingly, the therapy significantly limited the severity of disease when injected at the first sign of illness. So while the CAR T cells failed to efficiently deplete low affinity pathogenic helper T cells, they reacted more readily to alternate T cells which can cause disease.

The team then altered the CAR T cell design to further support the cells’ survival. In doing this, the CAR T cells gained higher sensitivity to both low and high affinity MOG-specific helper T cells.

Through this process, the researchers discovered a two-part mechanism that drives multiple sclerosis in animals. Based on the responses from the CAR T therapy, the team realized that higher affinity pathogenic T cells seem to initiate the disease, while their lower affinity counterparts seem to perpetuate the condition. As a result, the most comprehensive use of CAR T cells takes into consideration different stages of disease.

Implications

This CAR T therapy mouse model leaves room to hope for a long-sought cure for multiple sclerosis. The researchers successfully crafted CAR T cells which can target either low and high affinity helper T cells responsible for multiple sclerosis in mice. From these observations, CAR T therapy could be strategically used to either prevent disease or mitigate existing symptoms. If translated to humans, CAR T therapy could be administered to either prevent MS flare-ups or to thoroughly address already-existing symptoms.