More than 35,000 Americans this year will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer with an average five year survival rate of 58%. Preliminary study results by Johnson & Johnson and Legend Biotech suggest that their CAR T cell product may benefit multiple myeloma patients who received one to three previous lines of treatment. The clinical trial abstract has since been removed from the internet, as it appears to have been prematurely released. Nonetheless, the data appears promising and worth early discussion.

CAR T Therapy for Multiple Myeloma

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell therapy uses bioengineering and a patient’s own immune cells to treat their cancer. Genetic modification heightens the cancer-killing ability of a specific white blood cell called cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, aptly nicknamed “killer” T cells. The therapy received approval from the Food and Drug Administration to treat several kinds of blood cancers, including B cell lymphomas, certain leukemias, and multiple myeloma.

CAR T therapy for multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells, is a newer development. The FDA approved the intervention’s use for the first time in 2021, but under the condition that a patient tries at least five lines of treatment prior. This means that standard treatments such as a regimen of chemotherapy drugs (proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs), an antiCD38 monoclonal antibody or a stem cell transplant must fail before CAR T therapy becomes an option.

Research is underway to push CAR T therapy earlier in the queue. Bristol-Meyer Squibbs released Phase 3 clinical trials results in February this year demonstrating that their product Abecma reduced the risk of disease progression and death by 51% (compared to standard treatments) for patients who tried two to four prior treatments. J&J and Legend Biotech announced the unblinding of their own Phase 3 clinical trial CARTITUDE-4 in January, but for patients who received one to three prior lines of treatment. The preliminary results from this trial, as referenced here, should have been presented in May or June but instead was accidentally released last week.

Different CAR Structures

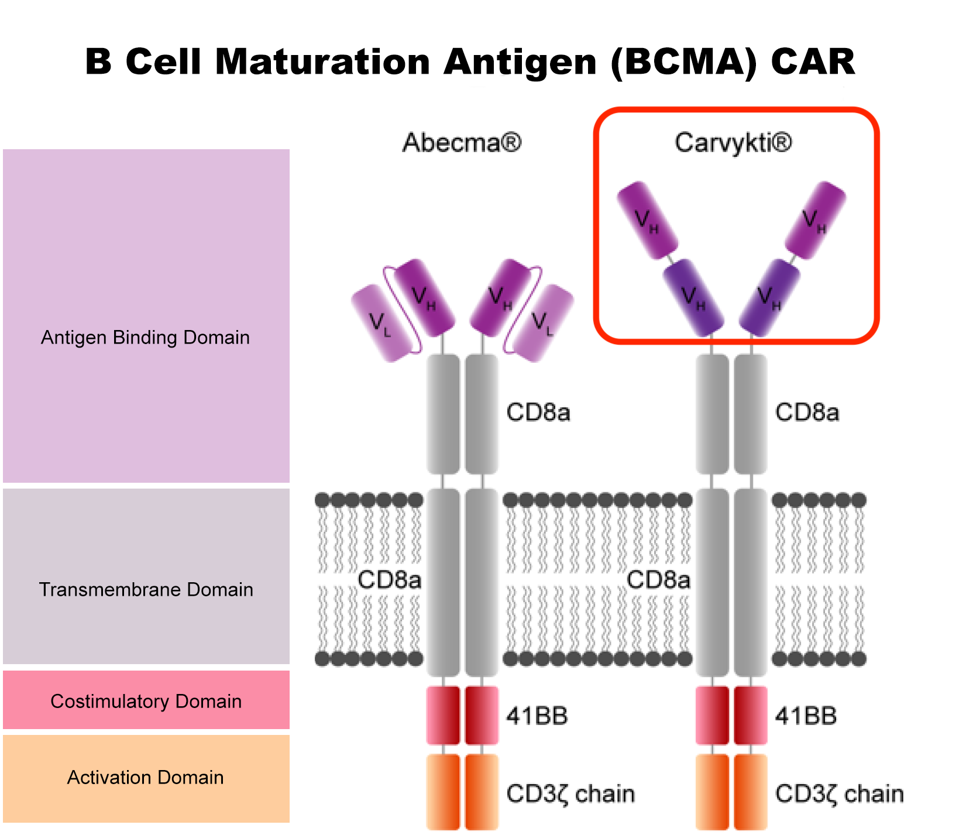

Is there a difference between the two therapies? In short, yes. Both CAR T cell products target a biological tag commonly found on the surface of plasma cells—B cell maturation antigen (BCMA)—but the method differs slightly.

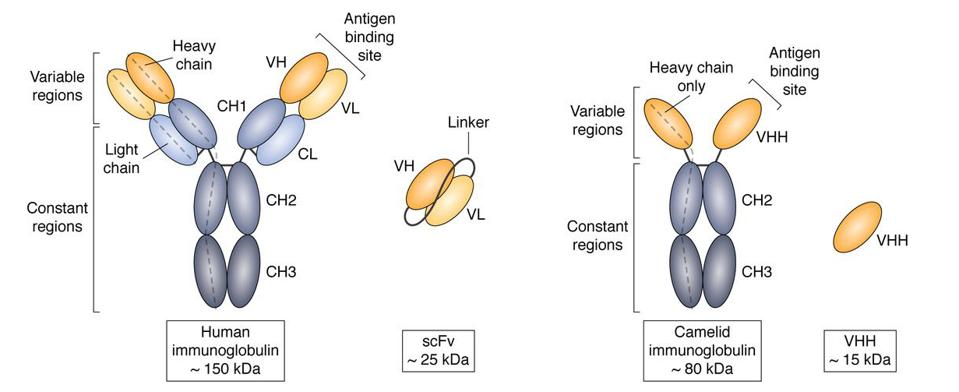

The exterior portion of Abecma’s chimeric receptor contains a single chain variable fragment. This fusion protein connects an antibody heavy chain fragment and light chain fragment by a flexible linker. It’s also commonly used in CAR T cell products for other blood cancers, albeit targeting a different antigen. In contrast, Carvykti uses a structure called a nanobody, also known as a single domain antibody (VHH) (see Figure 1).

A nanobody is derived from camelid animals such as llamas. It is nearly half the size of a single chain variable fragment, but retains a similar function and superior stability. It is also easier to manufacture in bulk. Carvykti uses two tandem nanobodies in their product, which allows the CAR T cell to bind to two regions of BCMA instead of one, as with Abecma. There is currently no evidence to suggest this mechanism has any clinical effect. Figure 2 compares the chimeric receptor structure of both products.

FIGURE 1: Size and structure comparison between a single chain variable fragment (scFV) and a camelid single domain antibody fragment (VHH), otherwise known as a nanobody. Nanobodies are derived from animals such as camels, llamas, and alpacas. Despite its small size, a nanobody can bind just as specifically as other antibodies. [Abbreviations: CH1, heavy chain constant domain 1; CH2, heavy chain constant domain 2; CH3, heavy chain constant domain 3; CL, light chain constant domain; IgG, immunoglobulin G; VH, heavy chain variable domain; VHH, single variable domain on a heavy chain; VL, light chain variable domain]

ACCESS HEALTH INTERNATIONAL, CHELOHA ET AL., 2020.

FIGURE 2: Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) comparison. The antigen binding domain differs between the two CAR T cell products. Carvykti specifically uses dual nanobodies in this region.

ACCESS HEALTH INTERNATIONAL, JOECHNER ET AL., 2022.

Promising Results

We already know that Carvykti performs well for patients whose cancer returns after four or more standard treatments. The first clinical trial for Carvykti illustrated how the intervention had an effect in almost all patients, and completely removed signs of cancer in around 78% of patients. Eventually this number increased to 83% according to a 28 month follow up.

How, then, does Carvykti perform when administered as an earlier treatment option?

The abstract suggests that Carvykti can elicit robust immune responses when administered earlier, as well. More than 400 patients were enrolled; around half received lymphodepletion chemotherapy (a preparatory measure) and CAR T therapy, while the other half received standard care. All underwent between one and three lines of treatment prior to the study before their cancer returned.

The study’s primary endpoint was met. A median 16 months of follow up revealed that Carvykti reduced the risk of disease progression/death by 74% compared to standard treatment—a major reduction in risk of relapse. Median progression-free survival (PFS) for the Carvykti group had not been reached; the researchers could not calculate this statistic because more than half of the group is still living, which is a positive sign. This is compared to a progression-free survival of 12 months for the patients under standard treatment.

In addition, the CAR T therapy elicited more robust responses than the control intervention. In fact, around 73% of patients saw a complete reduction in their cancer with CAR T therapy versus 22% under standard care.

The CAR T therapy and control safety profiles seem comparable, with 97% and 94% of patients (respectively) reporting serious adverse events. More than a third of Carvykti patients experienced cytokine release syndrome, a common adverse reaction to CAR T therapies. Notably, this adverse effect was not life-threatening. Neurotoxicity, another expected reaction, occurred in 5% of the CAR T therapy patients.

Future Implications

The study results deliver positive news. The CARTITUDE-4 trial demonstrates that anti-myeloma CAR T cells, applied sooner than later, can reduce the risk of relapse better than typical anti-myeloma treatments. This is not the first CAR T therapy moving its way to earlier lines of treatment. Research is proving that CAR T therapies, although previously considered a final resort for cancer patients, have the potential to enter the rotation of standard care. As shown here, efficacy and safety pose less of an issue than expected in achieving this dream.